What is the real price of getting rid of plastic packaging

3 September, 2018

How much would it cost to switch to plastic alternatives? Richard Gray crunches the numbers. bbcnews. July 06, 2018. Walking along a short section of stony beach, Claire Waluda stoops briefly to pick up something from between the rocks. It is a brightly coloured plastic bottle top – just one of hundreds of bits of plastic that she finds washed ashore on the remote, windswept island of South Georgia.

Located in the south Atlantic, on the fringes of the Antarctic, it is nearly 1,000 miles (1,500km) from the nearest major human settlement. Yet even here Waluda, an ecologist with the British Antarctic Survey, is finding worrying signs of our throw-away attitude towards plastic. Regularly she finds seals entangled in this debris or albatross chicks coughing up bits of plastic film.

These are just a few examples of the damage our throw-away relationship with plastics is inflicting on the environment. More than 78 million tonnes of plastic packaging is produced worldwide every year by an industry worth nearly $198 billion. Just a fraction of that is recycled while the vast majority is thrown away. Plastic litter now clutters every part of our planet, from remote parts of the Antarctic to the deepest ocean trenches.

High profile campaigns and TV programmes such as the finale of the BBC’s Blue Planet II, where Sir David Attenborough highlighted the problems plastics are causing in the world’s oceans, have led to growing public alarm over the issue. In response to mounting pressure, governments, manufacturers and retailers are beginning to take steps to tackle the tide of plastic waste. But how much will this fundemantal change to the way we buy our goods actually cost?

Many of the companies attempting to tackle the amount of plastic waste generated by their products admit it will eat into their profits. Coca-Cola, for example, produces 38,250 tonnes of plastic packaging in the UK each year and estimates indicate it sells more than 110 billion single-use plastic bottles globally. The company has pledged to double the amount of recycled material in its plastic bottles in the UK and is trialling refillable bottles. Although it refuses to give details, Coca-Cola says these efforts will increase costs.

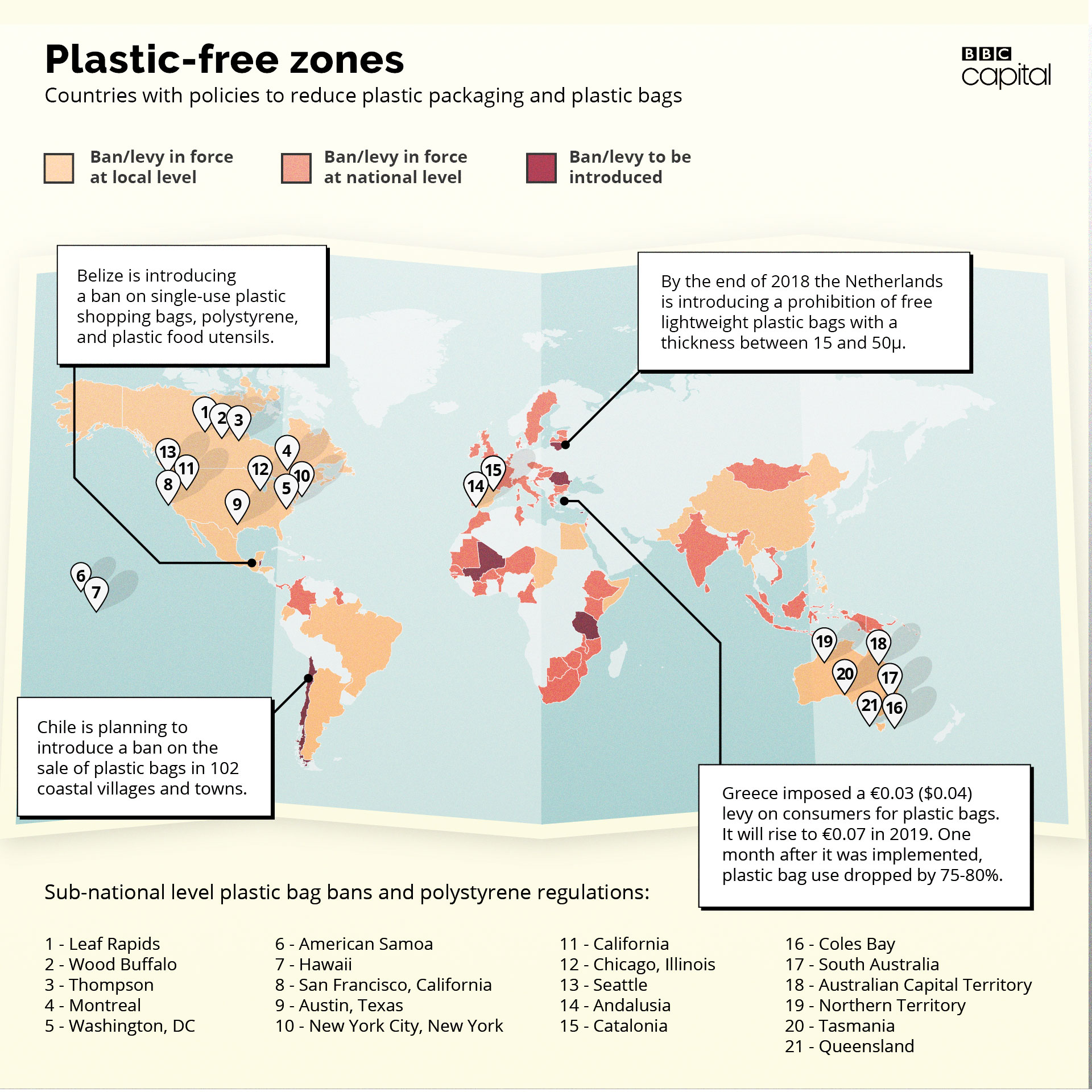

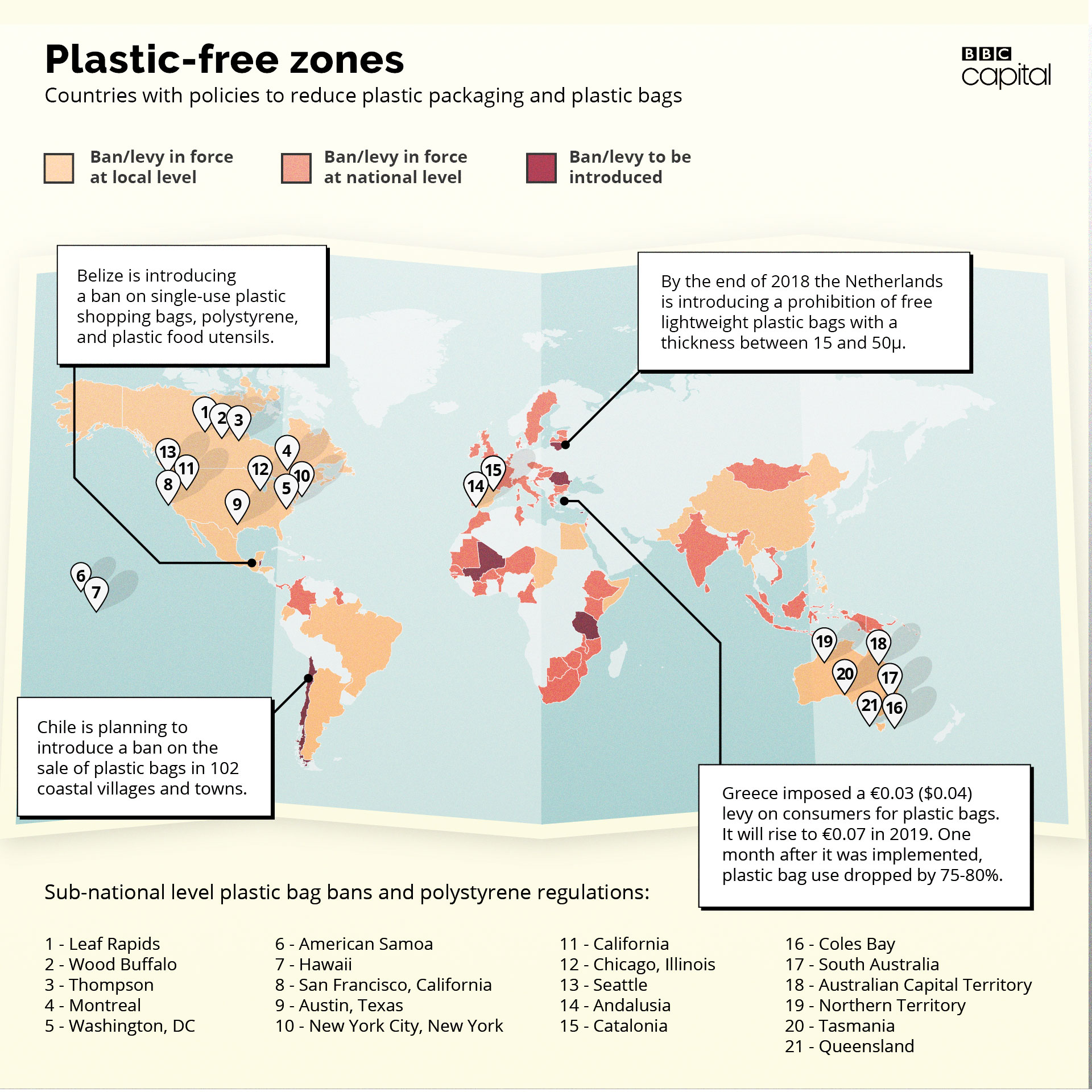

And even companies that have been dragging their heels will soon have to address the amount of plastic packaging they use. More than 60 countries are introducing legislation aimed at reducing the use of plastic bags and other single use plastic materials. This month, tiny Pacific island nation Vanuatu became the first in the world to ban single use plastic bags, straws and polystyrene food containers. About eight million metric tonnes of plastic are thrown into the ocean annually, according to data cited by Earth Day Network (Credit: Getty Images)The cost of change

About eight million metric tonnes of plastic are thrown into the ocean annually, according to data cited by Earth Day Network (Credit: Getty Images)The cost of change

Several major supermarkets, including multinationals Tesco and Walmart, have already promised to reduce the amount of plastic packaging they sell their products in. Alongside Coca-Cola, drinks manufacturers Pepsi, food and cleaning multinational Unilever, food producer Nestle and cosmetics company L’Oreal have also pledged to ensure all their packaging is either reusable, recyclable or compostable by 2025.

But despite these commitments, much of the food and drinks industry is still trying to work out how it will meet the targets it has helped to set for itself. Some experts fear that without the right approach, this rush to banish plastics from our shopping baskets will make the goods we buy more expensive.

“It is not as simple as ‘plastic is bad’ so let’s use something else,” warns Eliot Whittington, policy programme director at the University of Cambridge’s Institute for Sustainability Leadership, where he advises drinks manufacturers on reducing waste. “It will require a complete change in the way we use product packaging at the moment. Most packaging is now used just once and thrown away. We need to move away from that. It needs some form of leadership from government.”

More than 60 countries are introducing legislation aimed at reducing the use of plastic bags and other single use plastic materials (Credit: Getty Images)

More than 60 countries are introducing legislation aimed at reducing the use of plastic bags and other single use plastic materials (Credit: Getty Images)

Soft drinks plastic packaging makes up around 20% of the total food and drink packaging on the market, according to data from Coca Cola (Credit: Getty Images)

Soft drinks plastic packaging makes up around 20% of the total food and drink packaging on the market, according to data from Coca Cola (Credit: Getty Images)

Plastic films and protective trays keep fresh meat in an oxygen free atmosphere, helping to prevent it from spoiling (Credit: Getty Images)

Plastic films and protective trays keep fresh meat in an oxygen free atmosphere, helping to prevent it from spoiling (Credit: Getty Images)

These are just a few examples of the damage our throw-away relationship with plastics is inflicting on the environment. More than 78 million tonnes of plastic packaging is produced worldwide every year by an industry worth nearly $198 billion. Just a fraction of that is recycled while the vast majority is thrown away. Plastic litter now clutters every part of our planet, from remote parts of the Antarctic to the deepest ocean trenches.

High profile campaigns and TV programmes such as the finale of the BBC’s Blue Planet II, where Sir David Attenborough highlighted the problems plastics are causing in the world’s oceans, have led to growing public alarm over the issue. In response to mounting pressure, governments, manufacturers and retailers are beginning to take steps to tackle the tide of plastic waste. But how much will this fundemantal change to the way we buy our goods actually cost?

Many of the companies attempting to tackle the amount of plastic waste generated by their products admit it will eat into their profits. Coca-Cola, for example, produces 38,250 tonnes of plastic packaging in the UK each year and estimates indicate it sells more than 110 billion single-use plastic bottles globally. The company has pledged to double the amount of recycled material in its plastic bottles in the UK and is trialling refillable bottles. Although it refuses to give details, Coca-Cola says these efforts will increase costs.

And even companies that have been dragging their heels will soon have to address the amount of plastic packaging they use. More than 60 countries are introducing legislation aimed at reducing the use of plastic bags and other single use plastic materials. This month, tiny Pacific island nation Vanuatu became the first in the world to ban single use plastic bags, straws and polystyrene food containers.

About eight million metric tonnes of plastic are thrown into the ocean annually, according to data cited by Earth Day Network (Credit: Getty Images)The cost of change

About eight million metric tonnes of plastic are thrown into the ocean annually, according to data cited by Earth Day Network (Credit: Getty Images)The cost of changeSeveral major supermarkets, including multinationals Tesco and Walmart, have already promised to reduce the amount of plastic packaging they sell their products in. Alongside Coca-Cola, drinks manufacturers Pepsi, food and cleaning multinational Unilever, food producer Nestle and cosmetics company L’Oreal have also pledged to ensure all their packaging is either reusable, recyclable or compostable by 2025.

But despite these commitments, much of the food and drinks industry is still trying to work out how it will meet the targets it has helped to set for itself. Some experts fear that without the right approach, this rush to banish plastics from our shopping baskets will make the goods we buy more expensive.

“It is not as simple as ‘plastic is bad’ so let’s use something else,” warns Eliot Whittington, policy programme director at the University of Cambridge’s Institute for Sustainability Leadership, where he advises drinks manufacturers on reducing waste. “It will require a complete change in the way we use product packaging at the moment. Most packaging is now used just once and thrown away. We need to move away from that. It needs some form of leadership from government.”

More than a third of the food sold in the EU now comes packaged in plastic and each of its 510 million residents produce about 31kg of plastic packaging waste a year. One reason plastic is so dominant is its ability to do more, for less: it takes less material to make a drinks bottle out of plastic, for example, than it does to make one out of glass.

“Plastics are cheap, lightweight and adaptable in ways many of the alternatives are not,” says Susan Selke, director of the school of packaging at Michigan State University.

Fifty years ago, before the plastics revolution had gathered pace, most drinks were sold in glass bottles. Today almost all soft drink bottles are made from a tough plastic material called polyethylene terephthalate, or PET.

While the cost of producing bottles can vary depending on the raw material and energy prices at the time, it is generally not that much more expensive to produce a glass bottle versus one made from PET – about $0.01 more, according to some analysis.

However, when manufacturers start transporting produce in glass bottles, costs start to rise. A 330ml plastic soft drink bottle contains around 18 grams of material while a glass bottle can weigh between 190g and 250g. Transporting drinks in the heavier containers requires 40% more energy, producing more polluting carbon dioxide as they do and increasing transport costs by up to five times per bottle.

“In many cases plastics are actually better for the environment than the alternatives,” explains Selke. “It is surprising until you look closely at it.”

“Plastics are cheap, lightweight and adaptable in ways many of the alternatives are not,” says Susan Selke, director of the school of packaging at Michigan State University.

Fifty years ago, before the plastics revolution had gathered pace, most drinks were sold in glass bottles. Today almost all soft drink bottles are made from a tough plastic material called polyethylene terephthalate, or PET.

While the cost of producing bottles can vary depending on the raw material and energy prices at the time, it is generally not that much more expensive to produce a glass bottle versus one made from PET – about $0.01 more, according to some analysis.

However, when manufacturers start transporting produce in glass bottles, costs start to rise. A 330ml plastic soft drink bottle contains around 18 grams of material while a glass bottle can weigh between 190g and 250g. Transporting drinks in the heavier containers requires 40% more energy, producing more polluting carbon dioxide as they do and increasing transport costs by up to five times per bottle.

“In many cases plastics are actually better for the environment than the alternatives,” explains Selke. “It is surprising until you look closely at it.”

More than 60 countries are introducing legislation aimed at reducing the use of plastic bags and other single use plastic materials (Credit: Getty Images)

More than 60 countries are introducing legislation aimed at reducing the use of plastic bags and other single use plastic materials (Credit: Getty Images)A report by the American Chemistry Council and environmental accounting firm Trucost estimates that the environmental costs – which places a value on dealing with the pollution generated by a product – would be five times higher if the soft drinks industry used alternative packaging like glass, tin or aluminium instead of plastic. As governments seek to penalise polluting companies with carbon taxes and levies, these costs may be passed onto consumers.

“Food costs are going to increase – there can be no doubt about that,” says Dick Searle, chief executive of the British Packaging Federation, which represents the industry in the UK. Using glass milk bottles instead of plastic, for example, can lead to additional costs for producers.

But does this mean the costs will be passed back to shoppers?

Iceland, a British supermarket that pledged to remove plastics from its packaging by 2023, is already switching its ready meals from black plastic trays to ones made from paper and plans to use other packaging materials like glass and cellulose, which is made from wood.

“Making this change is going to cost money,” warns Richard Walker, the chain’s managing director. “But we are determined that our customers will not have to foot the bill.”

“Food costs are going to increase – there can be no doubt about that,” says Dick Searle, chief executive of the British Packaging Federation, which represents the industry in the UK. Using glass milk bottles instead of plastic, for example, can lead to additional costs for producers.

But does this mean the costs will be passed back to shoppers?

Iceland, a British supermarket that pledged to remove plastics from its packaging by 2023, is already switching its ready meals from black plastic trays to ones made from paper and plans to use other packaging materials like glass and cellulose, which is made from wood.

“Making this change is going to cost money,” warns Richard Walker, the chain’s managing director. “But we are determined that our customers will not have to foot the bill.”

Soft drinks plastic packaging makes up around 20% of the total food and drink packaging on the market, according to data from Coca Cola (Credit: Getty Images)

Soft drinks plastic packaging makes up around 20% of the total food and drink packaging on the market, according to data from Coca Cola (Credit: Getty Images)There are some, however, who warn that abandoning plastic after nearly 70 years of using it to package our food could have other far more costly, unintended consequences.

What may at first appear to be a wasteful plastic bag wrapped around your cucumber, for example, is actually a sophisticated tool for increasing the shelf-life of your food. Years of research have allowed plastics to push the time food lasts for from days to weeks.

“I think people underestimate the benefits of plastics in reducing food waste,” says Anthony Ryan, professor of chemistry and director of The Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures at the University of Sheffield.

The shrink wrap used on cucumbers for instance, can more than double the length of time the vegetable can last, allowing it to be kept for up to 15 days in the fridge and cutting food waste in half. An unwrapped cucumber would last just two days at room temperature and 9 days if refrigerated.

A meaty problem

Beef bought in polystyrene foam trays covered with plastic film will generally last between three and seven days. However if it is vacuum-packed in multilayer plastic, it can be kept for up to 45 days without spoiling. Environmental accounting firm Trucost estimate that vacuum-packing sirloin steak can cut food waste almost in half compared to conventional plastic.

Much of the food we now buy in supermarkets comes tightly wrapped in sealed plastic films and protective trays. This keeps fresh meat in an oxygen-free atmosphere, helping to prevent it from spoiling. Delicate fruit and vegetables are also kept safe from bumps that can degrade them, meaning they’re more likely to be sold. Putting grapes in their own individual plastic boxes has been found to cut food waste by 75%.

What may at first appear to be a wasteful plastic bag wrapped around your cucumber, for example, is actually a sophisticated tool for increasing the shelf-life of your food. Years of research have allowed plastics to push the time food lasts for from days to weeks.

“I think people underestimate the benefits of plastics in reducing food waste,” says Anthony Ryan, professor of chemistry and director of The Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures at the University of Sheffield.

The shrink wrap used on cucumbers for instance, can more than double the length of time the vegetable can last, allowing it to be kept for up to 15 days in the fridge and cutting food waste in half. An unwrapped cucumber would last just two days at room temperature and 9 days if refrigerated.

A meaty problem

Beef bought in polystyrene foam trays covered with plastic film will generally last between three and seven days. However if it is vacuum-packed in multilayer plastic, it can be kept for up to 45 days without spoiling. Environmental accounting firm Trucost estimate that vacuum-packing sirloin steak can cut food waste almost in half compared to conventional plastic.

Much of the food we now buy in supermarkets comes tightly wrapped in sealed plastic films and protective trays. This keeps fresh meat in an oxygen-free atmosphere, helping to prevent it from spoiling. Delicate fruit and vegetables are also kept safe from bumps that can degrade them, meaning they’re more likely to be sold. Putting grapes in their own individual plastic boxes has been found to cut food waste by 75%.

Plastic wrapping can also keep fruit and vegetables in their own little microclimates – known in the industry as modified atmosphere packaging – which can help to prevent them from ripening too quicky. Putting sweet peppers into a bag with a modified atmosphere can extend their lifespan from four days to 20, according to the Flexible Packaging Association. Extending the shelf life of food can greatly reduce the cost of food waste to supermarkets. Extending the shelf life of produce by just one day would save shoppers in the UK up to £500 million ($661m), according to anti-waste charity Wrap.

The global cost of food waste is already estimated to be almost $1 trillion a year, which is largely borne by manufacturers and retailers. While some believe that single-use plastic packaging has actually led to an increase in the amount of food we throw away by encouraging a culture of disposability, many in the plastics industry argue that without plastic packaging, the cost of food waste could rise.

The global cost of food waste is already estimated to be almost $1 trillion a year, which is largely borne by manufacturers and retailers. While some believe that single-use plastic packaging has actually led to an increase in the amount of food we throw away by encouraging a culture of disposability, many in the plastics industry argue that without plastic packaging, the cost of food waste could rise.

Smart thinking

In this light, it might not make sense to ban plastics altogether but instead make plastics better.

“Rather than going back, it is perhaps more useful to look at innovation,” says Eliot Whittington. “There are more and more companies that are reinventing plastics with additives that help them break down or making plastics that are biodegradable.”

Whittington points to the growing bioplastics industry, which uses starch or protein from plants like sugarcane to generate the basic hydrocarbon materials needed to create plastics. Some of these bioplastics are not biodegradable at all, but others – like polylactic acid (PLA) – can break down over time and some are compostable, meaning they disintegrate entirely rather than merely crumbling into smaller “microplastics”.

One company that has already shifted to bioplastic is British skincare company Bulldog. It has swapped its traditional plastic tubes for polyethylene made from sugarcane.

The new tubes are more expensive but “we still think it is the right thing to do,” says Simon Duffy, the company’s founder.

Another bioplastics leader is Coca-Cola, which two years ago launched the PlantBottle, a PET partially made with Brazilian sugarcane. It too has found that producing bottles from plants comes at a premium, although it wouldn’t share with BBC Capital what this cost was.

Looking at a few examples, however, it becomes apparent just how much more expensive bioplastics can be.

A burger box made from sugarcane for instance, is almost twice as expensive as one made from polystyrene. A biodegradable takeaway fork made from plant starch costs 3.5 times more than a basic white plastic one.

Neither Bulldog or Coca-Cola are using bioplastics that can be considered biodegradable or compostable, instead encouraging consumers to recycle their bioplastics. And, in fact, there is some resistance to the widespread use of biodegradable materials.

“Bioplastics like PLA are huge contaminate for traditional recycling,” says Dick Searle.

Surprisingly, due to rising oil prices, recycled plastic is actually cheaper to use than fresh, virgin plastic made from oil. A tonne of virgin PET costs around £1,000 while clear recycled PET costs just £158 per tonne.

Contamination of PET plastic with PLA, however, can leave the resulting bottle weaker and unfit for use, meaning the whole batch will have to be discarded. As manufacturers try to reduce their plastic footprint by using greener, biodegradable plastics, the risk of mixing with conventional plastics will only increase, potentially driving up the cost of recycled materials.

“Introducing these innovative products in a system that is used to more traditional waste stream is difficult economically,” says Whittington.

It is a problem that will require new ways of identifying, sorting and dealing with plastic materials when they are thrown away to ensure biodegradable materials are kept separate from those that can be recycled.

In this light, it might not make sense to ban plastics altogether but instead make plastics better.

“Rather than going back, it is perhaps more useful to look at innovation,” says Eliot Whittington. “There are more and more companies that are reinventing plastics with additives that help them break down or making plastics that are biodegradable.”

Whittington points to the growing bioplastics industry, which uses starch or protein from plants like sugarcane to generate the basic hydrocarbon materials needed to create plastics. Some of these bioplastics are not biodegradable at all, but others – like polylactic acid (PLA) – can break down over time and some are compostable, meaning they disintegrate entirely rather than merely crumbling into smaller “microplastics”.

One company that has already shifted to bioplastic is British skincare company Bulldog. It has swapped its traditional plastic tubes for polyethylene made from sugarcane.

The new tubes are more expensive but “we still think it is the right thing to do,” says Simon Duffy, the company’s founder.

Another bioplastics leader is Coca-Cola, which two years ago launched the PlantBottle, a PET partially made with Brazilian sugarcane. It too has found that producing bottles from plants comes at a premium, although it wouldn’t share with BBC Capital what this cost was.

Looking at a few examples, however, it becomes apparent just how much more expensive bioplastics can be.

A burger box made from sugarcane for instance, is almost twice as expensive as one made from polystyrene. A biodegradable takeaway fork made from plant starch costs 3.5 times more than a basic white plastic one.

Neither Bulldog or Coca-Cola are using bioplastics that can be considered biodegradable or compostable, instead encouraging consumers to recycle their bioplastics. And, in fact, there is some resistance to the widespread use of biodegradable materials.

“Bioplastics like PLA are huge contaminate for traditional recycling,” says Dick Searle.

Surprisingly, due to rising oil prices, recycled plastic is actually cheaper to use than fresh, virgin plastic made from oil. A tonne of virgin PET costs around £1,000 while clear recycled PET costs just £158 per tonne.

Contamination of PET plastic with PLA, however, can leave the resulting bottle weaker and unfit for use, meaning the whole batch will have to be discarded. As manufacturers try to reduce their plastic footprint by using greener, biodegradable plastics, the risk of mixing with conventional plastics will only increase, potentially driving up the cost of recycled materials.

“Introducing these innovative products in a system that is used to more traditional waste stream is difficult economically,” says Whittington.

It is a problem that will require new ways of identifying, sorting and dealing with plastic materials when they are thrown away to ensure biodegradable materials are kept separate from those that can be recycled.

Plastic films and protective trays keep fresh meat in an oxygen free atmosphere, helping to prevent it from spoiling (Credit: Getty Images)

Plastic films and protective trays keep fresh meat in an oxygen free atmosphere, helping to prevent it from spoiling (Credit: Getty Images)But Anthony Ryan sees other problems with the widespread use of biodegradable packaging.

“It treats the symptoms, not the disease,” he says. “If the disease is our throw-away society, making packaging biodegradable only encourages people to throw more away.”

Instead, he suggests another solution: use more plastic.

“In modern meat or soft fruit packaging you might have several thin layers to give it strength, to stop gas permeability and to act as an adhesive,” he explains. “You could get all of these properties from a single thicker piece of polyethylene. Then you would have a reduced set of materials, which would make separating and recycling this stuff easier.”

He believes that making plastics more durable could help solve the current waste problem that is blighting our planet. Rather than abolishing plastics altogether, he proposes reusing the packaging we currently throw away.

Already deposit and reuse schemes like this – where plastic bottles are returned in exchange for a cash deposit and then are refilled – are in use in Finland, Germany, Denmark and parts of Australia.

According to research by the European Commission, however, reuse and refill schemes like this can work out to be up to five times more expensive than using packaging once and then throwing it away. But the World Economic Forum found innovative reuse and refill measures could actually reduce packaging costs by at least $8 billion a year,savings that could potentially be passed onto consumers.

And as many countries seek to introduce new laws that will put new levies on plastic bags and ban certain types of single use packaging, refillable and reusable options may become more attractive.

For Claire Waluda, whose team is monitoring the levels of plastic waste in South Georgia, the price of making these changes is one worth paying.

“We are seeing wandering albatross parents feeding plastic to their chicks,” she says. “Anything that can reduce the amount of plastic debris in the environment is a step in the right direction.”

“It treats the symptoms, not the disease,” he says. “If the disease is our throw-away society, making packaging biodegradable only encourages people to throw more away.”

Instead, he suggests another solution: use more plastic.

“In modern meat or soft fruit packaging you might have several thin layers to give it strength, to stop gas permeability and to act as an adhesive,” he explains. “You could get all of these properties from a single thicker piece of polyethylene. Then you would have a reduced set of materials, which would make separating and recycling this stuff easier.”

He believes that making plastics more durable could help solve the current waste problem that is blighting our planet. Rather than abolishing plastics altogether, he proposes reusing the packaging we currently throw away.

Already deposit and reuse schemes like this – where plastic bottles are returned in exchange for a cash deposit and then are refilled – are in use in Finland, Germany, Denmark and parts of Australia.

According to research by the European Commission, however, reuse and refill schemes like this can work out to be up to five times more expensive than using packaging once and then throwing it away. But the World Economic Forum found innovative reuse and refill measures could actually reduce packaging costs by at least $8 billion a year,savings that could potentially be passed onto consumers.

And as many countries seek to introduce new laws that will put new levies on plastic bags and ban certain types of single use packaging, refillable and reusable options may become more attractive.

For Claire Waluda, whose team is monitoring the levels of plastic waste in South Georgia, the price of making these changes is one worth paying.

“We are seeing wandering albatross parents feeding plastic to their chicks,” she says. “Anything that can reduce the amount of plastic debris in the environment is a step in the right direction.”